The IBGE's National Household Sample Survey (PNADC), in addition to the characteristics of Brazilians, regularly investigates their housing conditions. In the part of the questionnaire related to housing issues, there are questions about the form of access to water, the existence of plumbing inside the home, the existence of a bathroom for exclusive use of domicile and the form of drainage of the sewage. In the edition of the 2016 survey, two matters of special sanitation interest were included. For households supplied by the general water distribution network, or by well and spring with pipeline, the IBGE asked if the supply was daily, or if it occurred with interruptions. The IBGE also asked if the home had a water tank or reservoir.

This chapter of the study is dedicated to analyzing how Brazilian women's access to sanitation was. In this analysis, conditions are considered in the various regions of the country, in urban and rural areas, in the metropolitan regions and in the capitals of the Federation units. The conditions of access to sanitation by age group, declared race, level of education and income class of Brazilian women are also investigated. In addition to PNADC data, some statistics on sewage treatment from the National Sanitation Information System (SNIS) of the Ministry of Cities are presented.

Access to Treated Water

In 2016, according to data from the PNADC, 90.8 million women report living in homes that received water through a general distribution network, corresponding to 85.7% of the female population. The frequency of women receiving treated water was higher in urban areas (93.7% of the population); in rural areas, only 34.7% of the women lived in homes connected to the general water distribution network. The capitals of the Federation units and the Federal District formed the group of cities with the best coverage: 95.2% of women received treated water in their homes. Statistics by region, area and capital are presented in Table A.1 of the Statistical Annex.

That year, 15.2 million women (or 14.3% of the population) reported not receiving treated water in their homes. This constituted a deficit of sanitation services, which was particularly high in the North (39.3% of the population) and Northeast (20.0% of the population). In the North, there are states with relatively low deficit in the access to treated water, such as Roraima (11.5% of the population), Tocantins (12.9% of the population) and Amazonas (25.4% of the population), and there are those with high deficits - Rondonia (55.9% of the population), Para (47.6% of the population), Acre (46.4% of the population) and Amapá (41.4% of the population). In the Northeast, the states that were most advanced in the process of universalization of treated water were Sergipe, with a deficit of 14.0% of the population, Bahia, with 14.5% of the population, and Rio Grande do Norte, with 14.7% of the population. Deficits were highest in Maranhão and Alagoas, where respectively 32.1% and 25.2% of the female population lived in households without access to the treated water distribution system.

Map 2.1

Number of women without water supply through general network, per thousand people and (% of female population), 2016

Source: IBGE, 2017. Elaboration: Ex Ante Consultoria Econômica.

Lack of treated water was concentrated in younger women. In the age groups from 0 to 4 years of age and from 4 to 9 years of age, the access deficit to treated water exceeded 17% of the respective female populations in these ranges. The higher the age, the lower the frequency of women in the access deficit to treated water, with only 10.9% of the female population lacking treated water in the age group of women aged 80 or over.

Graph 2.1

Women's access to the general water distribution network, by age group, 2016

Source: IBGE, 2017. Elaboration: Ex Ante Consultoria Econômica.

Deficits in access to treated water was relatively higher in populations of self-reported multiracial and indigenous women. In these two groups, the percentage of women who did not receive treated water in their homes exceeded 18% of the female population. Among self-reported women of Asian descent, only 5.9% lived in housing without access to treated water in 2016. In the case of self-reported white women, the frequency of women in the deficit was also less than the average (10.6% of the population).

Graph 2.2

Access by women to the general water distribution network, by declared race, 2016

Source: IBGE, 2017. Elaboration: Ex Ante Consultoria Econômica.

According to IBGE estimates, the lack of access to treated water was higher in the female population with lower schooling. In the group of uneducated women, the share without access to the water distribution system reached 21.6% of the population. In the group of women who completed higher education, the incidence of women in the treated water deficit was only 5.1% of the population.

Graph 2.3

Women's access to the general water distribution network, by level of education, 2016

Source: IBGE, 2017. Elaboration: Ex Ante Consultoria Econômica.

The incidence of women without access to the treated water distribution system was particularly high among the poorest income classes. Among the households that belonged to the poorest 10% of the country, the incidence of women without access to treated water reached 31.9% of the population, while among the 10% richest households in the country, the incidence was of only 4.2%. With regard to this group, it is worth mentioning that, for the most part, they were women living in houses on remote farms. For that reason, in 2016, 38.8% of the women without access to the treated water distribution system belonged to the first quintile and 24.0% to the second quintile of the per capita household income distribution in Brazil.

Graph 2.4

Distribution by income class of the access deficit to the general water network of the female population, 2016

Source: IBGE, 2017. Elaboration: Ex Ante Consultoria Econômica.

Regularity in Supply

Besides the lack of access to the water distribution system, the lack of regularity in the water supply also affected the quality of life of the population. Irregular water supply can be as harmful as the lack of access itself, as deprivation, even if temporary, has health consequences. For this reason, the guidelines of the Federal Government's National Plan for Basic Sanitation (Plansab) only consider as adequate the system that guarantees the uninterrupted supply of treated water through a general distribution network, in the case of urban housing, or well, spring or cistern, with internal conduit, in the rural households. Only the daily supply of water is considered uninterrupted. The consideration that adequate is the daily delivery is based, on one hand, on the recommendation that the Brazilian houses have, on average, 466 liters of water supply (1 In engineering terms, a minimum of 157 liters of water per inhabitant is recommended. (200 liters for apartments and 150 liters for houses). Considering the national average of 2.97 inhabitants per household in 2016, there is a need of 466 liters per household) and, on the other hand, the fact that the average consumption in the country, through the supply networks, was 477 liters per day per household in 2016, according to information from the National Sanitation Information System (SNIS) of the Ministry of Cities. It should also be considered that a significant part of the Brazilian housing (10.3 million, or 14.9% of the total housing in the country) did not even have a water tank or reservoir according to PNADC data for 2016.

PNADC statistics for 2016 indicate that of the 90.8 million Brazilian women living in housing connected to the general water distribution network, only 78.8 million women reported receiving water on a daily basis. This means that only 74.4% of Brazilian women had regular access to treated water, a proportion 11.4% lower than that of women living in houses connected to the general water distribution network.

As indicated by statistics by region, area and capital, which are presented in Table A.2 of the Statistical Annex, the greatest differences occurred in the metropolitan regions, where the percentage of women with access to the general water distribution network was 88.6% and that of women who received regularly treated water in their homes of 70.2% - a difference of 18.4 percentage points. In regional terms, considering all the areas, the situation of the Northeast stands out. In this region, the percentage of women with access to the general water distribution network was 80.0% and that of women who received regularly treated water in their homes of only 53.2%, indicating a difference of 26.8 percentage points. The states with the greatest differences between the two coverage rates were Pernambuco (42.8 percentage points), Paraiba (37.9 percentage points) and Rio Grande do Norte (34.3 percentage points).(2 In Paraíba and Rio Grande do Norte, most of the differences came from outside the metropolitan areas. In Pernambuco, on the other hand, the problem was concentrated in the metropolitan region: there, the percentage of women with access to the general water distribution network was 89.4%, and women receiving treated water regularly in their homes of only 39.4%, indicating a difference of 50 percentage points.) The situation in the State of Amazonas also draws attention, since the difference between the percentage of women with access to the network and that of the female population receiving regular water was 31.6 percentage points.

Statistics show that by 2016, 12 million women lived in homes connected to the general water distribution network, but water was not regularly delivered to their homes. This corresponded to 13.2% of the Brazilian female population. According to data from the PNADC, in 40% of these cases, water was distributed between 4 and 6 days a week, 45.7%, between 1 and 3 days a week and in 14.2% of cases, regularity was less than 1 day per week.

Graph 2.5

Distribution by age group of women who do not receive water regularly, 2016

Source: IBGE, 2017. Elaboration: Ex Ante Consultoria Econômica.

The age distribution of these 12 million shows a strong concentration among adult women aged between 20 and 59 years. This age group concentrated 56.6% of women with access to the general network, but without regular supply of water. Women of up to 19 years old accounted for 28.5% of these cases and women over 60 years old accounted for 14.9%.

Graph 2.6

Share of the female population that does not receive regular water, by race declared, 2016

Source: IBGE, 2017. Elaboration: Ex Ante Consultoria Econômica.

As in the case of lack of access to the general distribution network, the incidence of irregular deliveries is higher among self-declared multiracial women (17.5% of the total) and black women (15.7%). These two groups accounted for 67.8% of the 12 million women with irregular access to treated water. The incidence in the group of self-declared white women was only 8.9% of the total of this population and of the self-reported women of Asian descent, of 7.7%.

Graph 2.7

Share of the female population that does not receive regular water, by level of education, 2016

Source: IBGE, 2017. Elaboration: Ex Ante Consultoria Econômica.

Something similar occurred in the distribution of these women by level of education. As in the case of the simple lack of access to the general distribution network, the incidence of network access with irregular deliveries was also higher among women with lower levels of education. The percentage of people with access to a network that provided irregular deliveries reached 18.3% of uneducated women. This percentage fell to 7.5% in the case of women with a higher education degree.

The PNADC statistics also reveal the concentration of these cases in the lower economic classes. About 30% of the 12 million women who reported living in households with access to the general water distribution network, but receiving water with interruptions, belonged to households in the first quintile of household income distribution per capita. Other 25% belonged to the second quintile, indicating that almost 55% of these women were among the poorest 40% of the Brazilian population. Among women who belonged to the first quintile of the per capita household income distribution, the incidence of persons with irregular supply was 16.8%, while among the richest women, who were in the fifth quintile of income distribution, the incidence was of only 5.6%.

Graph 2.8

Distribution by income class of the female population that does not receive water regularly, 2016

Source: IBGE, 2017. Elaboration: Ex Ante Consultoria Econômica.

Consideration of irregular supply as a deficit corrects estimates of the number of women with access to treated water services to more realistic levels. As shown in Map 2.2, the number of women in the deficit zone of regular access to treated water reached 27.2 million by 2016. This indicates that one in four women either had no access to treated water or did not receive regular access to it. This proportion reached almost one in two women in the North and Northeast regions of Brazil. In the female population, the Brazilian states with the greatest relative water deficits were: Acre (78.0%), Pernambuco (64.3%), Rondonia (60.5%), Paraiba, (60.1%), Para (55.3%), Maranhao (51.8%), Rio Grande do Norte (49.0%), Amapa (43.5%) and Alagoas (41.2%). In absolute terms, it is worth noting that the water deficit due to access or regularity in the female population of the Brazilian Southeast was still very high: in Rio de Janeiro there were more than 2.1 million women in this situation, in Sao Paulo, more than 2 million, and in Minas Gerais, more than 1.5 million.

Map 2.2

Number of women with no regular water supply, per thousand people and (% of female population), 2016

Source: IBGE, 2017. Elaboration: Ex Ante Consultoria Econômica.

Sewage System

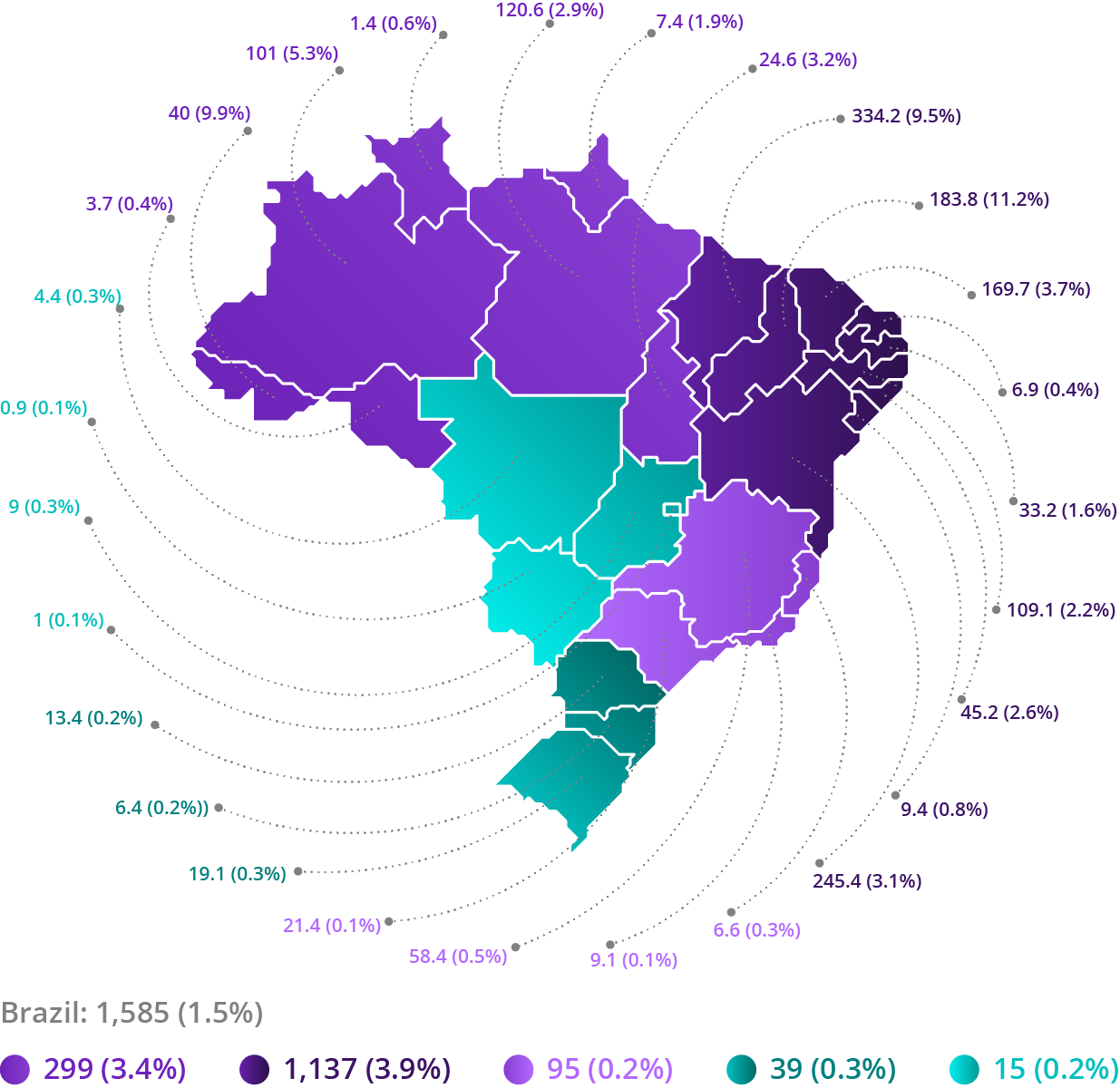

The lack of a bathroom at home is the most primary of the problems associated with sewage. This problem afflicted 1.585 million Brazilian women in 2016, according to PNADC data.

As Map 2.3 points out, there was a huge concentration of this phenomenon in the Northeast, which accounted for 71.7% of Brazilians in this condition. In the region, the incidence rate of women living in households without a bathroom reached 3.9% of the female population in that year. The situation was also serious in the North, where the incidence rate was 3.4%. The number of people in the North of Brazil under these conditions reached almost 300,000 women, representing 18.8% of the national total of women in housing without bathroom. (3 The Northeast and North rates of women with no bathroom for exclusive use in the household are close to the averages found in less developed Latin American countries such as Panama and Honduras. The Instituto Trata Brasil study (2017) presented international indicators of access to sanitation.)

Map 2.3

Number of women without a bathroom in the household, in a thousand people and (% of the female population), 2016

Source: IBGE, 2017. Elaboration: Ex Ante Consultoria Econômica.

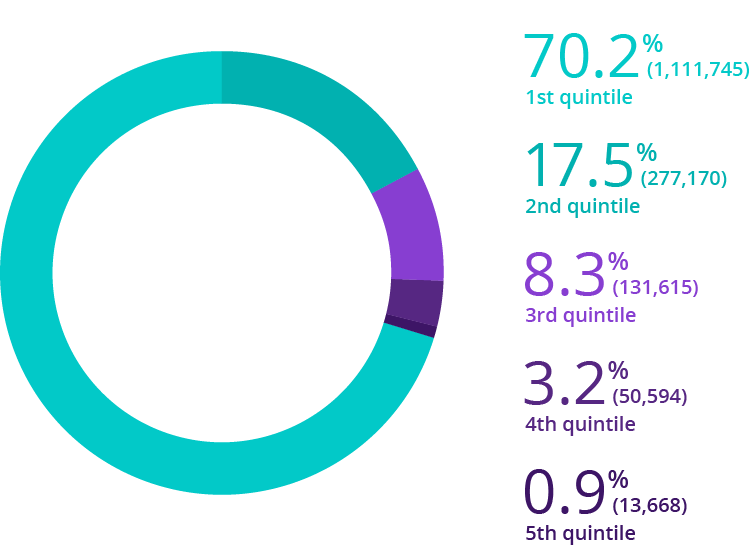

Women without a bathroom in the household lived mostly in homes that belonged to the first quintile of the per capita household income distribution of 2016. In this income class, there were 1,121 million women, which represented 70.2% of Brazilian women in these conditions. The incidence rate of women without a bathroom for exclusive use of the household in this income class reached 5.2% of the women in the first quintile of the household income distribution per capita.

Graph 2.9

Distribution by income class of the female population that does not have a bathroom in the house, 2016

Source: IBGE, 2017. Elaboration: Ex Ante Consultoria Econômica.

For the people who lived in homes with bathrooms, the question that arises is the adequacy of the collection of residential sewage. Again, based on the guidelines of the National Plan for Basic Sanitation (Plansab), it is considered adequate housing that is connected to the general network of sewage collection (urban areas) or septic tank (rural areas). The households where sewage waste goes to a rudimentary pit not connected to the general network, to ditches or are dumped directly into rivers and lakes or into the sea are inadequate.

In 2016, only 79.1 million women (or 74.6% of the 105.9 million Brazilian women) lived in housing where the sanitation disposal system was considered adequate. This indicates that one in four Brazilians did not have an adequate system, a frequency similar to water inadequacy (due to lack of access to the system or interruption). Table A.4 of the Statistical Annex details these statistics by region.

Due to the fact that, in rural areas, adequacy is achieved with smaller investments and depends only on the decision of the residents themselves, the adequacy indexes seem to be higher in the Brazilian countryside than the indexes registered in the cities. In the rural areas of the country, 81.0% of the women lived in housing with adequate sanitary disposal. In urban areas, only 73.6% of the women lived in homes with adequate disposal. As a result, the absolute and relative deficit of sanitary disposal affected more the inhabitants of the urban areas of the country: in 2016, there were 24.2 million women in inadequately-disposing houses in Brazilian cities and 2.7% rural areas. The metropolitan areas concentrated 32.5% of the female and urban population without access to the general sewage collection network and the other cities of the country, 67.5%. This indicates that the problem afflicted relatively the small and medium Brazilian cities that did not belong to metropolitan regions. In these areas, one in three women lived in an urban residency without sewage collection through the general network.

In 2016, 26.9 million women (or 25.4% of the female population) reported living in homes without adequate sewage disposal. This constituted another deficit of sanitation services, also high in the North (67.3% of the population) and Northeast (39.0% of the population). In the North region, there are states with deficits in access to adequate sanitary disposal relatively low, as were the cases of Tocantins (56.4% of the population) and Acre (56.8% of the population), and there are those with relatively high deficits - Para (71.3% of the population) and Amapa (85.5% of the population). In the Northeast, the states that were most advanced in the process of universalizing the collection of sewage were Bahia, with a deficit of 24.9% of the population, and Sergipe, with a deficit of 25.2% of the female population. The deficits were higher in Piaui and Maranhao, where respectively 72.1% and 64.7% of the female population lived in households without adequate sanitary sewage.

Map 2.4

Number of women without sewage collection, in thousand people and (% of female population), 2016

Source: IBGE, 2017. Elaboration: Ex Ante Consultoria Econômica.

The 2016 PNADC found that lack of access to an adequate form of sanitary disposal was more frequent among children. Among women up to 4 years of age, 69.6% lived in housing with adequate disposal conditions and 30.4% in houses with inadequate disposal of sewage. Among women older than 80 years, the adequacy was achieved by 81.8% of the female population and the inadequacy affected 18.2% of the people.

Graph 2.10

Women's access to the sewage collection system, by age group, 2016

Source: IBGE, 2017. Elaboration: Ex Ante Consultoria Econômica.

The adequacy levels of the sanitary sewage were higher in the white female population or in the Asian descending population. Adequate sanitary sewage deficits were, consequently, relatively minor. Among self-reported white women, 17.9% did not live in homes with adequate sewage and among self-reported of Asian descent, only 11.0%. On the other hand, the deficits were higher among self-reported multiracial, indigenous and black women: in these groups, the incidence of inadequate sanitation was 24.3%, 33.0% and 40.9% of the respective female populations.

Graph 2.11

Women's access to the seweage network by self-declared race, 2016

Source: IBGE, 2017. Elaboration: Ex Ante Consultoria Econômica.

In line with what happened with access to treated water, the lack of proper disposal conditions has further afflicted women with lower income and lower levels of education. Among uneducated women, the sanitation deficit reached 32.6% of the population, while the rate was only 14.5% among women with higher education in 2016. In the group of women who belonged to the first quintile of the distribution of per capita household income, the incidence rate of women in housing without adequate sanitary disposal reached almost 40%. Among the richest women, who belong to the fifth quintile, the incidence was only 12.7%. For this reason, the poorest women accounted for 31.7% of the female population in the deficit of adequate sanitary sewage and the richest, for only 9.9% of the total.

Graph 2.12

Women's access to the sewage collection system, by educational level, 2016

Source: IBGE, 2017. Elaboration: Ex Ante Consultoria Econômica.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that, in addition to the lack of adequate sanitary sewage, a large part of the sewage collected in the general networks was not properly disposed, because it did not receive treatment before disposal in the environment. For this untreated portion, collection only served to move sewage away from residences. According to preliminary data from SNIS 2016, only 74.1% of the sewage collected in the country received treatment before disposal. The remaining 25.9% of the collected sewage was discarded in natura in rivers, lakes or in the sea.

Considering the volume of water billed by the operators (of water or water and sewage) in each region, the volume of treated sewage corresponded to an even smaller fraction. In 2016, only 39.8% of the volume of water delivered was collected and treated prior to disposal. This implies a sewage treatment deficit of more than 60% in the country. As Map 2.5 illustrates, the deficit was relatively large in the North and Northeast regions of Brazil. But the problem also plagued the Southern and Southeastern states. In Santa Catarina, only 18.6% of the volume of water delivered and billed was collected and treated, that is, the treatment deficit reached 81.4%. In Minas Gerais, which had the third largest water consumption in the country, the treatment deficit reached 63.4% of the volume of water billed.

Deprivation Profile

The previous analysis show how Brazilian women's access to sanitation was in 2016. In the various dimensions of the analyzed sanitation deficit, there were women of all races, ages, schooling levels and classes of household income. They were in all regions: from the North to the South, in the urban and rural areas, in the capitals and in the interior.

Map 2.5

Sewage treatment deficit: (%) of the volume of billed water that is not collected and treated, 2016

Source: SNIS, 2018. Elaboration: Ex Ante Consultoria Econômica.

However, some characteristics are predominant and influence the chances of a woman being deprived of basic sanitation services. These characteristics emerged not only from the description of the statistics collected in the study but also from more detailed econometric analysis that sought to identify the determinants of the sanitation deficit. These analysis, set out in detail in the Methodological Appendix of this study, allow to separate the partial effects of each analyzed dimension, considering that some characteristics in general occur simultaneously - for example, indigenous and black self-declared women have, on average, lower education, and more often belong to poorer families.

The analysis confirmed some correlations that make it possible to trace more likely profiles of deprivation. In summary, the woman without adequate access to treated water belonged to a family among the poorest 30% of Brazil, she had low education - mostly had incomplete primary education -, she was adolescent or young (less than 40 years old), lived in metropolitan areas of the country or in rural areas. The woman without access to adequate sewage services had a similar profile, with the distinction that she lived in urban areas of the countryside of the country.

Graph 2.13

Distribution of the access deficit to the sewage collection system by income class, 2016

Source: IBGE, 2017. Elaboration: Ex Ante Consultoria Econômica.

These aspects give a very marked social connotation to the issue of access to basic sanitation in Brazil, not only in the income aspect, but also in the precariousness of services, precisely in the most vulnerable social groups. The conclusions also raise several issues ranging from effective access to treated water to heterogeneous management capacity among the medium and small municipalities of the country. Finally, the analysis suggest that the impacts of lack of sanitation on women's lives may occur more frequently in specific groups of the female population. Therefore, these consequences of deprivation of sanitation need to be analyzed in greater detail, a task that will be developed in the next chapters of the study.